I have the unfortunate habit of shooting myself in the foot sometimes, intellectually speaking. I devalue something because it’s too easy, but can’t complete something else because it’s too hard.

So this speech (#7: “Research your topic”) when I kept hitting a wall, I took the easy road. I took an essay I wrote years ago to satisfy a three-points-and-a-conclusion Nazi. Then I upgraded it (to this version you’re about to see on the blog), then I cut it down to a 5-7 minute speech.

The whole thing felt horribly formulaic and “cheap,” and the points seemed so self-evident I wasn’t sure if it would count as “research,” but I got the job done, and it was even a job I could be proud of, so it all worked out in the end.

Maybe what I’m trying to learn is that easy doesn’t have to mean without value.

Maybe I could just call it straightforward.

Main critique of the speech: I need to be more aware of ambient noise in a room so I can try and match my volume to the needs of the space. This I appreciated. One of my goals is to teach more on specialized topics like these, so I’m glad when someone gets specific about presentation.

It tickled me to hear my evaluator say how I’d clearly researched my topic. I do suppose he’s right– it just happened so long ago it doesn’t feel like research any more :)

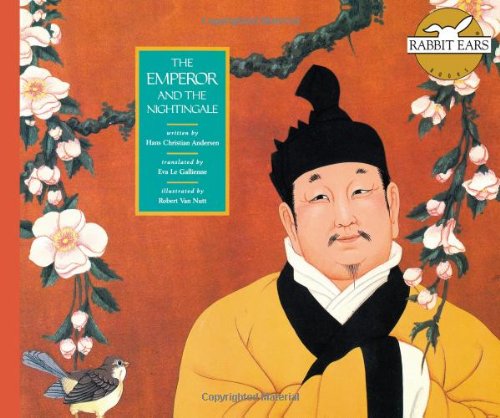

I began by reciting this section of Anderson’s The Nightingale in my best storytelling rhythm.

Death kept staring at the emperor out of the empty sockets in his skull; and the palace was still, so terrifyingly still.

All at once the most beautiful song broke the silence. It was the nightingale who had heard of the emperor’s illness and torment. She sat on a branch outside his window and sang to bring him comfort and hope.

As she sang… the blood pulsed with greater force through the emperor’s weak body.

Death himself listened and said, “Please little nightingale, sing on!”

“Will you give me the golden saber? Will you give me the imperial banner? Will you give me the golden crown?”

Death gave each of his trophies for a song; and then the nightingale sang about the quiet churchyard, where white roses grow…and where the grass is green from the tears of those who come to mourn.

Death longed so much for his garden that he flew out of the window, like a white cold mist.

“Thank you, thank you, whispered the emperor, “you heavenly little bird, I remember you…. When you sang…Death himself left my heart. How shall I reward you?”

“You have rewarded me already,” said the nightingale. “I shall never forget that, the first time I sang for you, you gave me the tears from your eyes; and to a poet’s heart, those are jewels.”

There are as many different ways to tell stories as there are storytellers, but somehow we all know when we’ve heard a good one.

According to Albert Lavin, and English Teach and author, Stories, “are a way of organizing human response to reality…they are a fundamental aspect of the way we ‘process’ experience.”

A good story affects our feelings, our perspectives, sometimes even our world, if only for a blip of time. If it is a significant story, the change will be more permanent.

One desire of storytellers is to cause what is significant for the teller to become significant for a listener.

Flannery O’Connor, a famous short-story writer, observed, “A story is a way to say something that cannot be said any other way…. You tell a story because a statement would be inadequate.”

With this goal in mind, of conveying significance, a good storyteller has many tools to help her. Elements that have been a part of telling as long as there has been language.

Three of these are establishing the setting, using repetition effectively, and knowing the audience. These are among the foundation-stones of effective storytelling. Once one has a story, these elements can bring life to it, both for the teller and the listeners.

First, the setting is a storyteller’s canvas. It may look as simple as a watercolor wash or be as complex as a many-layered oil painting.

Events and characters will be built upon it. However, it is (usually) only the background. The busier the background, the more sophisticated listeners will have to be to distinguish the action from the setting.

For younger listeners, especially, a highly detailed landscape can obscure the happenings of a story. This isn’t just because children are less sophisticated, however. In the words of William Kirkpatrick, Professor of Education at Boston College, “Children are deeply concerned with serious questions,” and simplicity should be only for clarity, not in order to dilute a story.

Hans Christian Anderson, who wrote what I just shared, was a master storyteller skilled in establishing setting.

He begins that story, The Nightingale with the words, “In China, as you know, the Emperor is Chinese, and so are his court and all his people.”

The audience is efficiently transported halfway around the world with only a few words.

The detailed description of the setting that follows can be simplified for fidgety ears or left complete.

The trick is to maintain the balance between the foreground and the background, providing a setting for the characters without distracting from what they do.

Another tool to make listeners more at home in the story is repetition, which can take on several forms.

For example, repetition can create a refrain. This is especially useful with young children. Many will eagerly join in singing with the ornery cookie, “Run, run as fast as you can. You can’t catch me, I’m the Gingerbread Man!”

Such a refrain can create an expectation that may later be thwarted for great affect, which may also begin teaching the rudiments of irony.

In the story of The Three Billy Goats Gruff, repetition comes in the sinister form of the hungry troll under the bridge. Repetition becomes the point of fear, and conflict. The cessation of that ominous repetition signals, especially to young listeners, that all is now well.

A more subtle form of repetition can be observed in The Nightingale.

Some details are revisited in a way that draws upon remembering the earlier occurrence. When the Emperor’s tears fall for the second time, in the excerpt earlier, their significance to the bird is explained.

A more mature reader or listener may already understand, but by revisiting the topic, Anderson makes sure everyone knows. Tidbits like these are a sort of reward for those who have been paying attention; each reference has meaning on its own, but gains greater significance when connected with the other events.

Another type of repetition used in stories is the type that just fits nicely into the cadence of speech. Often in sets of three, these sentences of parallel construction are used as spells, chants and turning points in many stories.

In The Nightingale, Death asks the little bird to sing again and the nightingale replies, “Will you give me the golden saber? Will you give me the imperial banner? Will you give me the golden crown?” and the bird reclaims the Emperor’s treasures with a song.

Like many good tales, The Nightingale is enjoyed by all ages, but how much each listener gleans depends on the way it is told.

The use of repetition and the setting in a telling both affect the way a particular audience will respond.

Sometimes, though it may grieve the teller, rich details must be left out. But in the end the point is to tell the story: a character is introduced, a conflict arises, and is resolved. The attack on cultural illiteracy continues. If nothing more, an appetite may be whetted for the real thing.

Storytellers must put the story on and tailor it to the needs of their audience– and the time.

The full text of The Nightingale takes nearly half an hour to read aloud.

This is doable for some adults, or with a child used to looking at one picture for an extended period, but is rather too long for inexperienced hearers. The slow pace of the story is not helpful for those not used to sitting and listening to one picture-less story that length of time.

Which elements are retained and how they are balanced depends on their purpose in a particular story.

In order to leave out a subtle repetition that explains something, the tears in The Nightingale for example, the audience must be mature enough to draw their own conclusions or the detail can’t matter.

Many details can be left out poetic tales without the storyline suffering, and so they often are. The text can go from plush velvet to practical denim as the details are taken away– still entirely functional, only less elegant.

The job of the storyteller is to take the tools available, including setting, repetition and understanding the audience, and make them serve the larger purpose of the story itself.

Anderson’s opening in The Nightingale goes on to say,

“This story happened a long, long time ago; and that is just the reason why you should hear it now, before it is forgotten.”